- Home

- about stbrigits

- Human Resources Considerations

- The Rights of a Parish Priest

Simply Catholic and Welcoming You

The Rights of a Parish Priest

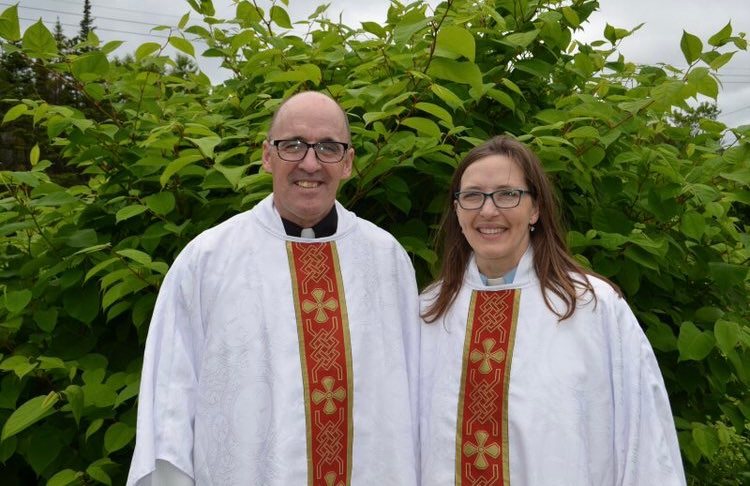

Two Parish Priests Who's Rights are Protected by Canon Law

The rights of a parish priest are not negated by their vows of respect and obedience to their Episcopate. For reference we will use the Roman/Latin Rite Code of Canon Law.

While a priest’s ministry is dependent upon that of his bishop, and every priest vows respect and obedience to the bishop at ordination, it is a common mistake to think of a pastor as a kind of branch manager of the bishop. The pastor’s canonical role is much different from that.

Canon law treats the subject of a 'parochus' — the pastor of a parish — very explicitly.

Canon 515 §1 of the Code of Canon Law says that each parish is to be entrusted to the care of a parochus, who serves as the shepherd of the community under the authority of the bishop.

The same canon makes clear that the parish itself is not a piece of land, a church or any other collection of buildings. A parish is properly understood as a group of the faithful, usually defined as those living in a particular area.

The relationship between the pastor and his parish is, in a technical sense, personal: a relationship between persons, defined and circumscribed by law.

In canon law, every parish has its own “juridic personality,” meaning that is a freestanding legal entity, with its own property and its own rights and obligations.

The code clarifies that the pastor represents the parish “in all juridic affairs,” and it is his responsibility to lead the community and decides what is in its best interests.

Of course, the bishop is free to establish policies for all parishes in his diocese — called particular laws — provided that they do not conflict with universal canon law or divine law. But within the boundaries established by canon law, divine law and civil law, it is the pastor’s job to lead the parish and to determine, prayerfully and in consultation, how best to govern the community with which they have been entrusted.

The Rights of a Parish Priest:

Priests and Bishops Can Disagree

Two Priests and a Bishop Celebrate Mass and Consecrate the Holy Eucharist

The rights of a parish priest are protected under Canon Law and they maintain all rights granted under the laws of the land in which they minister.

There have been cases where the parish priest (the head priest or lead priest for the parish) and the bishop disagree about parish needs, and canon law provides mechanisms to address such conflicts, including processes of appeal from episcopal decisions and directions and canonical courts in which they can be adjudicated.

Provided both sides agree to it, mediation can be used to resolve differences less intensely or with less conflict. Such mediation may involve the College of Bishops or outside professional mediation, depending on the matter to be resolved.

A bishop and pastor/parish priest might disagree, for example, about parish property. A bishop may direct a pastor to sell a piece of property or to give it over to meet a diocesan need, and the pastor may judge that to be a bad idea. Such a dispute could become a matter of “hierarchical recourse,” if the pastor appeals a decision he does not support. When disputes over such matters are appealed to Rome, (in our case to the College of Bishops) the Congregation for Clergy is often obliged to remind the bishop to respect the rights of the pastor.

Similarly, within the scope of universal and particular canon law and the teachings of the Church, a pastor also has the autonomy to teach and preach in a way he believes is best suited to the needs of the people.

This does not mean, of course, that bishops have no authority over parish pastors. In addition to establishing particular laws for his diocese, a bishop has the authority to oblige any priest or member of the faithful to do, or not do, a particular thing he may determine to be detrimental to the wider community. He can do this through a precept, a kind of canonical injunction directed at a specific person or situation.

Since a precept is a formal legal action, a pastor has the right to appeal it, provided he does so according to the procedures established by canon law. But he does not have the right to simply ignore a legitimately issued precept.

Bishops also have the authority to appoint pastors. Except for very exceptional cases, canon law gives the diocesan bishop a free choice to appoint the priest he thinks is most suitable for the job. This is understandable, since the pastor carries out his role “under the authority of the diocesan bishop in whose ministry of Christ he has been called to share.”

Still, due to the rights of a parish priest being protected, a bishop is not free to remove or transfer a pastor from his office without following a detailed and nonnegotiable process defined by canon law. This procedure can only be initiated if a priest has met one or more conditions for removal outlined in the law, which include actions “gravely detrimental or disturbing to ecclesiastical communion,” along with permanent infirmity of mind or body, a loss of good reputation among his flock, and neglect of his duties in the parish.

Even if a priest has met those conditions, before he can be removed from the office of pastor, the bishop must formally consult with certain priests appointed by the diocesan priests’ council, he must allow the pastor the opportunity to see the evidence against him and make a defense, and he must discuss that defense with the priests appointed to consult with him.

During this whole process, the bishop can neither remove the pastor nor appoint a replacement.

If the bishop does issue a decree of removal, the rights of a parish priest ensure they have the right to appeal their case to Rome, (our College of Bishops) where the Congregation for Clergy, or eventually the Apostolic Signatura, can examine the decision and the process used to reach it.

A bishop also has the prerogative, in certain limited circumstances, to declare that a priest is impeded from exercising priestly ministry, but that must be done through a delineated process, as well. A bishop could also withdraw certain faculties for ministry from a priest, but only if he has good reasons, and only if he has followed the procedural requirements of canon law.

This can include restrictions up to and including what laity call 'defrocking' the priest. The ordination to priesthood is permanent in that it is a sacrament thus, once received it cannot be somehow withdrawn or taken back.

That said, in a specific and lengthy process and only 'for cause' i.e. proven wrongdoing, the priesthood authority can be restricted or removed, temporarily or permanently. Meaning that a priest, found to be seriously in the wrong, can be restricted from preaching, saying mass or officiating in any capacity at any of the sacraments normally within the expected duties of the priesthood.

Effectively, they remain ordained but are no longer allowed to act as a priest. Think of getting your drivers licence but then committing an offence resulting in the suspension or revocation of your licence. The knowledge and training are still yours but the authority to use them (to drive) has been removed. This is not the same but helps understand the process better.

Despite the protected rights of a parish priest, this is important for a variety of reasons including legal liabilities purposes. A priest found guilty of serious wrongdoing could always have been subjected to this process rather than being rebuked and moved to another parish to repeat their offences.

Indeed moving a known offender to allow them to repeat their offences may, in itself make the bishop complicit in the further offences. Thus the bishop can be criminally charged and or the church exposed to civil liability.

In short, while no priest has a right to an assignment or to ministry, once a priest is appointed a pastor, he cannot be removed from his office, or from his ministry, without serious cause and without observation of the law’s procedural requirements. (Similarly, where applicable prohibiting a priest from residing in a certain place can only be done in the limited circumstances allowed by canon law.)

This also means that, except in very limited and unusual circumstances, a bishop is not within his rights to attempt to remove the legitimate pastor of a parish from its property or to threaten to have the police do so. Were a bishop to do such a thing without observing canonical requirements, and the priest appeal, it is likely that the Vatican (our College of Bishops) would order the pastor to be reinstated.

Neither can a bishop compel any priest to undergo a psychological evaluation or engage in psychological treatment. While a bishop might condition future assignments on a “clean bill of mental health,” he cannot force a priest to be diagnosed or treated against his will, or to disclose the details of his mental health if he does not wish to do so.

Canon 519 says that the pastor exercises “the pastoral care of the community committed to the pastor under the authority of the diocesan bishop in whose ministry of Christ he has been called to share, so that for that same community he carries out the functions of teaching, sanctifying and governing.”

The authority of the diocesan bishop is not absolute; nor is the autonomy of the pastor. But both exist, as defined by canon law, for the service of the Church and the salvation of souls. Understanding the authority of bishops and the rights of pastors is important in order to avoid or mediate conflicts and to protect the rights of the priests from uninformed, unethical or abusive oversight.

Recent Articles

-

Ordination, incardination and dismissal of clergy

Mar 03, 25 06:47 PM

Overview of Ordination to Holy Orders, incardination and dismissal of clergy -

Catholic Last Rites

Mar 03, 25 06:41 PM

An explanation of the Catholic Last Rites and Anointing of the Sick -

Catholic-Confession

Mar 03, 25 06:37 PM

Full breakdown of the Catholic Confession Sacrament of Reconciliation